Sortir and Partir are two irregular French verbs with very similar meanings. But we don’t always use them in the same way! For example:

Sortir: Je sors du travail à 18h. = I [get out of] work at 6 pm.

Partir: Je pars du travail, j’arrive bientôt. = I’m leaving work, I’ll arrive soon.

Both verbs can be loosely translated to “I’m leaving” in French. But what does each verb really mean, and how can we use them more fluently in French conversation? Let’s learn.

C’est parti !

Want all the vocabulary of the lesson ?

1) Sortir / Partir: Overview

Basically:

- Sortir = to get out, to go out (from somewhere)

- Partir = to leave (indefinitely)

But these are very broad translations, and they don’t match perfectly.

We mainly use sortir when getting out of a specific place, like a room or a building. And it’s mostly limited in time.

For example:

En sortant de la boulangerie, j’ai trébuché.

= When I walked out of the bakery, I stumbled. (or “While walking out of the bakery…”)

(Yes, “walking out” and other specific verbs, are translated as sortir in French.)

Je sors faire les courses.

= I’m going out to buy groceries.

Je sors cinq minutes, je dois passer un coup de fil.

= I’m getting out (of the room) for five minutes, I have to make a phone call.

In English, you might say: “I’m leaving the room for five minutes.” But in French, when we’re talking about leaving a room, it’s much more natural to use sortir instead of partir.

That’s because partir is more indefinite. You’re going somewhere further away, and for a long time.

For instance:

Désolée, je dois partir. = I’m sorry, I have to leave / I have to go.

(It’s a polite way to take your leave in French.)

Je pars de chez moi le mois prochain.

= I’m leaving my place next month. / I’m moving away next month.

→ Je sors de chez moi le mois prochain would mean “I’m only going outside next month.”

There’s some overlap, though!

Je sors du travail à 18h. = I’m getting out of work at 6, I’m leaving work at 6.

Je pars du travail à 18h. = I’m leaving work at 6.

With sortir, you emphasize that you’re getting out of something or some place. With partir, you emphasize that you’re leaving for somewhere else. That’s a very subtle difference, though. Both versions work in everyday French.

In French, quitter is another verb that means “to leave.” There’s always an object after it:

Quitter un endroit = to leave a place

Quitter quelqu’un = to leave someone / to break up with someone

And “to quit” is “abandonner” in French!

See also: Laisser = “to let” or “to leave something (where they are) / not taking something with you.”

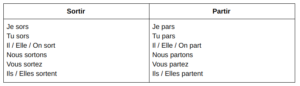

2) Conjugation

Sortir and Partir are both irregular, third group verbs.

In the present, they make:

3) Sortir / Partir : Idiomatic uses

Nous sortons le gâteau du four. = We’re taking the cake out of the oven.

Tu penses à sortir le chien ? = Can you think about walking the dog?

(Yes, you can say sortir quelque chose = to take something out. You can NOT say “partir quelque chose,” though!)

We also use sortir for:

Sortir (avec des amis) = Going out (with friends.)

→ On sort ce soir ? = Are we going out tonight?

Sortir avec quelqu’un = to date someone

→ Tu sors avec Julie ? Oui, on sort ensemble depuis deux mois.

= Are you dating Julie? Yes I am, we’ve been dating for two months now.

Sortir = to be released (for a cultural work)

→ Le film sort l’année prochaine. = That movie gets released next year.

→ Mon livre sort bientôt. = My book will get released soon, will be published soon.

S’en sortir = to escape, to be alright in the end.

→ Si on ne fait rien, on ne va jamais s’en sortir. = If we do nothing, we’ll never get out of that situation.

→ Il s’en sort bien, pour un nouveau. = He’s making a good job of it, for a new guy.

***

Meanwhile, partir also gets some idiomatic uses.

C’est parti ! means “It’s gone / It’s started,” or basically: “let’s go!” (and you cannot use sortir in its place!)

Partir de can also mean “to start from.”

→ Il est parti de rien, il a tout fait lui-même. = He started from nothing, he did everything by himself.

→ On part de loin, mais on va y arriver. = We’re starting from faraway (with a big handicap, with a lot to do) but we’ll make it.

Partir is also used for general travel.

Partir en vacances = to go on vacation.

→ Elles partent souvent en vacances en été. = They often go on vacation in the summer.

Partir dans un autre pays = to leave for another country.

→ Je pars au Kazakhstan en avril. = I’m leaving for Kazakhstan in April / I’m going to Kazakhstan in April.

Un train / un bus… part. = A train or a bus is leaving a place.

→ Le train part dans cinq minutes. = The train is leaving the station in five minutes.

“Un sort” is a noun that means “a magic spell,” “an outcome,” “luck” and more. But it’s not related to sortir.

***

Une part is a noun that means “a slice” or “a fraction of something.” It has several uses, and doesn’t match cleanly with the English “a part” (though they are synonyms in some context.) Either way, it’s not related to partir.

4) Sortir / Partir : Your Turn Now

Enough with all these explanations! It’s your turn now.

Gain fluency with these subtle differences and practice some sentences for yourself. Say them out loud, repeat them, get them in your head, and they’ll come more naturally later on!

For example:

Je sors de la pièce pour passer un coup de fil.

= I’m leaving the room to make a phone call.

On part en vacances la semaine prochaine.

= We’re going on vacation next week.

Sors de ta chambre, viens voir le soleil !

= Get out of your room, come and see the sun!

Partir, c’est mourir un peu.

= Leaving is a little bit like dying. (French proverb)

La vérité sort de la bouche des enfants.

= Truth comes out of children’s mouth. (French proverb)

Congratulations!

Learn more with these other lessons:

– Arriver vs Venir: French verbs with subtle differences

– The Only 7 French Verbs To Learn First

– Understand Spoken French with Andrea from Call My Agent.

À tout de suite.

I’ll see you in the next lesson!

And now:

→ If you enjoyed this lesson (and/or learned something new) – why not share this lesson with a francophile friend? You can talk about it afterwards! You’ll learn much more if you have social support from your friends 🙂

→ Double your Frenchness! Get my 10-day “Everyday French Crash Course” and learn more spoken French for free. Students love it! Start now and you’ll get Lesson 01 right in your inbox, straight away.

Click here to sign up for my FREE Everyday French Crash Course

Thank you so much Geraldine ! This lesson helped me a lot!

Merci beaucoup ☺️ you help me a lot in understanding the difference between these verbs which totally were confusing me when i should use “Sortir et Partir”

Great news, Nagla!

Merci, Geraldine. Pourriez-vous expliquer la différence entre se souvenir et se rappeler? Les deux sont aussi similaires, mais différents, n’est pas.

Bonjour Marie !

Shortest answer:

It’s the same thing, don’t worry.

Longer answer :

It’s basically the same thing, except that when there’s an object after it, we add “de” after “se souvenir”.

Se souvenir **de** [quelque chose] = Se rappeler [quelque chose]

Je me souviens de ma première chute de vélo.

= Je me rappelle ma première chute de vélo.

= I remember the first time I fell of a bike.

Longest answer:

It’s rare to forget the “de” after “se souvenir” – but on the other hand, a lot of French people make the mistake of adding “de” after “se rappeler”. So it’s a mess.

I feel like there’s also a subtle difference in the way we use it – as in, we’d rather use “se souvenir” for people and “se rappeler” for situations. But people would also say “Tu te rappelles de moi ?” (= Do you remember me? – with the mistake “rappeler de”) instead of the correct “Tu te souviens de moi ?” – Because “Tu me rappelles ?” (which would be the correct construction with “se rappeler [quelqu’un]”) sounds weird.

But really, I recommend you go with the shortest answer when having a French conversation 🙂

Have a great day,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française

Thanks Geraldine. Your explanation makes it clear.

It seems that Partir relates pretty closely to Depart in English. If that’s accurate it would make it easy to remember

J’ajoute ma voix à douzain de “Merci”, Géraldine. La vidéo a été organisé et expliqué de manière clair et intéressante. Et Joyeuses Pâques si vous célébrez.

Merci beaucoup Géraldine c’est très utile

Bonne journée Anne

Merci pour cette leçon, c’est très utile

Merci beoucoup !

Merci Géraldine, votre explication est très claire.

Superb. Merçi

You do a great job, madame.

Salut Géraldine!!

Merci pour le leçon!!

J’ai appris qu’il fallait “passer un coup de fil !!”

«Faire un appel» est canadien?

Bisous

Brian

Salut Brian !

En effet, on n’utilise pas “faire un appel” en France. On peut dire “passer un coup de fil” / “passer un coup de téléphone” / “passer un appel” (rare) / “téléphoner” / “appeler quelqu’un”… ou si quelqu’un nous téléphone, c’est “recevoir un appel” / “avoir un appel” / “quelqu’un qui m’appelle”…

Mais si tu dis “faire un appel” en France, les gens comprendront ! Et ce sera amusant – c’est beau la diversité des accents et vocabulaire.

Bonne journée,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française